سلطنت عثمانیہ دے دور وچ مسلماناں اُتے ظلم و ستم

سلطنت عثمانیہ دے زوال تے تحلیل دے دوران، مسلم (بشمول عثمانی ترک ، البانیائی ، بوسنیاکس ، سرکیسیئن ، سرب مسلمان ، یونانی مسلمان ، مسلم روما ، پومکس ) [۱] انہاں علاقےآں وچ رہنے والے باشندے جو پہلے عثمانی کنٹرول وچ سن، اکثر اپنے آپ نوں اک دے طور اُتے پایا۔ سرحداں نوں دوبارہ کھینچنے دے بعد اقلیت نوں ستایا گیا۔ ایہ آبادی نسل کشی، قبضے، قتل عام تے نسلی تطہیر دا نشانہ بنی سی۔ [۲][۳]

۱۹ويں صدی وچ بلقان وچ قوم پرستی دا عروج عثمانی اقتدار دے زوال دے نال ہويا، جس دے نتیجے وچ اک آزاد یونان ، سربیا تے بلغاریہ تے رومانیہ دا قیام عمل وچ آیا۔ اک ہی وقت وچ ، روسی سلطنت دا دائرہ قفقاز تے بحیرہ اسود دے علاقے دے سابقہ عثمانی زیرِاقتدار یا عثمانی اتحادی علاقےآں وچ پھیل گیا۔ انہاں تنازعات نے وڈی تعداد وچ مسلمان مہاجرین نوں جنم دتا۔ پہلی جنگ عظیم دے دوران مشرق وچ حملہ آور روسی فوجیاں تے ترکی دی جنگ آزادی دے دوران اناطولیہ دے مغرب، مشرق تے جنوب وچ یونانیاں تے آرمینیائیاں دے ذریعے مسلماناں اُتے ظلم و ستم دوبارہ شروع ہويا۔ یونانی ترک جنگ دے بعد، یونان تے ترکی دے درمیان آبادی دا تبادلہ ہويا، تے یونان دے بوہتے مسلمان اوتھے توں چلے گئے۔ انہاں دناں وچ بوہت سارے مسلمان مہاجرین، جنہاں نوں مہاجر کہیا جاندا اے، ترکی وچ آباد ہوئے۔

پس منظر

سودھوترکی دی موجودگی تے بلقان وچ مقامی لوکاں دی اسلامائزیشن

سودھوپہلی بار، عثمانی فوجی مہمات ۱۳۵۰ دی دہائی وچ جزیرہ نما گیلیپولی اُتے قبضے دے نال اناطولیہ توں یورپ تے بلقان دی طرف منتقل ہوئیاں۔ [۴] مسلم سلطنت عثمانیہ دی طرف توں اس خطے نوں فتح کرنے دے بعد، ترکی دی موجودگی وچ وادھا ہويا۔ آباد کاراں وچوں کچھ Yörüks سن، خانہ بدوش جو جلدی توں بیٹھ گئے سن، تے ہور شہری طبقات توں سن ۔ اوہ تقریباً تمام قصبےآں وچ آباد ہو گئے، لیکن انہاں دی اکثریت مشرقی بلقان وچ آباد ہوئی۔ آباد کاری دے اہم علاقے لڈوگوری ، ڈوبروڈزہ ، تھراسیئن میدان، شمالی یونان دے پہاڑ تے میدانی علاقے تے دریائے وردار دے آلا دُوآلا مشرقی مقدونیہ سن ۔

۱۵ويں تے ۱۷ويں صدی دے درمیان بلقان دے مقامی لوکاں دی وڈی تعداد نے اسلام قبول کیا ۔ وڈے پیمانے اُتے تبادلاں دیاں تھانواں بوسنیا ، البانیہ ، شمالی مقدونیہ ، کوسوو ، کریٹ تے روڈوپ پہاڑاں وچ سن ۔ [۵] مقامی آبادی وچوں کچھ نے اسلام قبول کیا تے وقت دے نال ترکی بن گئے، خاص طور اُتے اناطولیہ وچ ۔ [۶]

ظلم و ستم دے محرکات

سودھوہال دسدے نيں کہ بلقان دے تنازعات دے دوران ہر طرف توں مظالم ڈھائے گئے۔ جان بجھ کر دہشت گردی نوں مخصوص علاقےآں توں آبادی دی نقل و حرکت اُتے اکسانے دے لئی ڈیزائن کيتا گیا سی۔ شہری آبادی نوں نشانہ بنانے دا مقصد نسلی طور اُتے یکساں ملکاں نوں تراشنا سی۔ [۷]

عظیم ترک جنگ

سودھوترکی دی عظیم جنگ (۱۶۸۳–۱۶۹۹) توں پہلے وی آسٹریا تے وینیشیناں نے ہرزیگووینا ، مونٹی نیگرو تے البانیہ دے عیسائی فاسد تے باغی پہاڑیاں دی مسلم غلاماں اُتے چھاپہ مارنے دے لئی حمایت دی سی۔ [۸]

عظیم ترکی جنگ دے خاتمے دے بعد پہلی بار سلطنت عثمانیہ نے وڈے علاقے عیسائیاں دے ہتھ توں کھو دیے۔ ہنگری ، پوڈولیا ، تے موریا دا بیشتر حصہ کھو گیا سی۔ عثمانیاں نے جلد ہی موریہ نوں دوبارہ حاصل کر ليا، تے مسلمان جلد ہی آبادی دا حصہ بن گئے یا پہلے کدی مکمل طور اُتے بے گھر نئيں ہوئے۔

سلطنت عثمانیہ وچ رہنے والے بوہتے عیسائی آرتھوڈوکس سن، اس لئی روس نوں انہاں وچ خاص دلچسپی سی۔ ۱۷۱۱ وچ پیٹر دتی گریٹ نے بلقان دے عیسائیاں نوں عثمانی مسلم حکمرانی دے خلاف بغاوت دی دعوت دتی۔ [۹]

ہنگری

سودھوپیش دے محاصرے دے بعد، مقامی مسلماناں نوں ۱۶۸۶ تے ۱۷۱۳ دے درمیان کیتھولک مذہب اختیار کرنے اُتے مجبور کيتا گیا، یا ایہ علاقہ چھڈ دتا۔ [۱۰] ہتوان شہر ترک تاجراں دے لئی اک پناہ گاہ بن گیا تے مسلماناں دی اکثریتی بستی بن گیا، لیکن ۱۶۸۶ وچ ہنگری دی فوجاں دے قبضے وچ آنے دے بعد، تمام ترک آباد کاراں نوں زبردستی بے دخل کر دتا گیا تے شہر وچ انہاں دا قبضہبودا دی آزادی وچ لڑنے والے غیر ملکی کرائے دے فوجیاں دی ملکیت بن گیا۔ [۱۱]

کروشیا

سودھوسولہويں صدی وچ سلوونیا وچ رہنے والے تمام لوکاں وچوں اک چوتھائی مسلمان سن جو بوہتے قصبےآں وچ رہندے سن، جس وچ اوسیجیک تے پوجیگا سب توں وڈی مسلم آبادیاں سی۔ [۱۲] دوسرے مسلماناں دی طرح جو کروشیا ( لیکا تے کورڈون) تے ڈالمتیا وچ رہندے تھے ، اوہ سب ۱۶۹۹ دے آخر تک اپنے گھر چھڈݨ اُتے مجبور ہو گئے۔ ایہ اس خطے وچ مسلماناں دی صفائی دی پہلی مثال سی۔ مسلماناں دی اس صفائی نے "کیتھولک چرچ دے احسانات دا لطف اٹھایا" کروشیا تے سلاونیا توں تقریباً ۱۳۰٬۰۰۰ مسلماناں نوں عثمانی بوسنیا تے ہرزیگووینا بھیج دتا گیا۔ [۱۳][۱۴] بنیادی طور پر، تمام مسلمان جو کروشیا، سلاوونیا تے ڈالمتیا وچ رہندے سن یا تاں جلاوطنی اُتے مجبور، قتل یا غلام بنائے گئے۔ [۱۵]

ہزاراں سرب پناہ گزیناں نے ڈینیوب نوں عبور کيتا تے ہیبسبرگ بادشاہت دے آبادی والے علاقےآں نوں مسلماناں نے چھڈ دتا۔ لیوپولڈ اول نے باقی مسلم آبادی نوں کوئی مراعات دتے بغیر انہاں نوں نسلی مذہبی خودمختاری دتی جو اس وجہ توں اوتھے دے ہور مسلماناں وچ عیسائی مخالف جذبات پھیلاندے ہوئے بوسنیا، ہرزیگووینا تے سربیا بھج گئے۔ [۱۶] بلقان دے زیر قبضہ عثمانیاں دی غیر مسلم تے مسلم آبادی دے درمیان تعلقات بتدریج خراب ہُندے گئے۔ [۱۷]

۱۸ويں صدی دے شروع وچ سلاونیا دے باقی ماندہ مسلمان پوساوینا چلے گئے۔ [۱۸][۱۹] عثمانی حکام نے بے دخل کيتے گئے مسلماناں دی اپنے گھراں نوں جلد واپسی دی امیداں دی حوصلہ افزائی دی تے انہاں نوں سرحدی علاقےآں وچ آباد کيتا۔ [۲۰] مسلمان لکا دی تقریباً ۲/۳ آبادی اُتے مشتمل سن ۔ انہاں سب نوں، کروشیا دے دوسرے حصےآں وچ رہنے والے مسلماناں دی طرح، کیتھولک مذہب اختیار کرنے یا نکالنے اُتے مجبور کيتا گیا۔ [۲۱] کروشیا وچ عثمانیاں دے جانے دے بعد تقریباً تمام عثمانی عمارتاں تباہ ہو گئياں۔ [۲۲]

شمالی بوسنیا

سودھو۱۷۱۶ وچ ، آسٹریا نے ۱۷۳۹ تک شمالی سربیا دے نال نال شمالی بوسنیا اُتے قبضہ کيتا جدوں بلغراد دے معاہدے وچ ایہ زمیناں سلطنت عثمانیہ نوں واپس دے دتیاں گئیاں۔ اس دور وچ ، آسٹریا دی سلطنت نے اپنی انتظامیہ دے اندر رہنے دے بارے وچ بوسنیائی مسلم آبادی دے سامنے اپنا موقف بیان کيتا۔ چارلس VI دی طرف توں دو آپشنز پیش کيتے گئے سن جداں جائیداد نوں برقرار رکھدے ہوئے عیسائیت اختیار کرنا تے آسٹریا دی سرزمین اُتے باقی رہنا، یا باقی رہنے والے مسلماناں دی دوسری سرزمین اُتے روانگی۔ [۲۳]

مونٹی نیگرو

سودھو۱۸ويں صدی دے آغاز وچ (۱۷۰۹ یا ۱۷۱۱) آرتھوڈوکس سرباں نے مونٹی نیگرو وچ اپنے مسلمان پڑوسیاں دا قتل عام کيتا۔ [۲۴][۲۵]

قومی تحریکاں۔

سودھوسربیا دا انقلاب

سودھودہیجی دے بعد، متعصب جنیسری جنہاں نے سلطان دی مخالفت کيتی تے سمیدیریوو دے سنجاک اُتے ظلم (۱۸۰۱ دے آغاز وچ ) حکومت کیتی، سخت ٹیکس تے جبری مشقت عائد کردے ہوئے، ۱۸۰۴ وچ پورے سنجاک وچ سربست سرباں نوں پھانسی دینے دے لئی اگے ودھے، سرباں نے داجی دے خلاف اٹھیا کھڑے ہوئے۔ . بغاوت، جسنوں پہلی سربیائی بغاوت دے ناں توں جانیا جاندا اے، بعد وچ سرباں دی فوری کامیابی دے بعد قومی سطح اُتے پہنچ گئی۔ پورٹ نے، سرباں نوں اک خطرہ دے طور اُتے دیکھدے ہوئے، انہاں نوں ختم کرنے دا حکم دتا۔ انقلابیاں نے ۱۸۰۶ وچ بلغراد اُتے قبضہ کر ليا جتھے عام شہریاں سمیت اک مسلم گیریژن دے خلاف مسلح بغاوت ہوئی۔ [۲۶] بغاوت دے دوران وڈے پیمانے اُتے مسلم آبادی والے شہری مراکز نوں پرتشدد طریقے توں نشانہ بنایا گیا جداں اوژیشتے تے وایئور ، کیونجے سربیا دے کساناں نے شہری مسلم اشرافیہ توں طبقاتی نفرت دا اظہار کيتا سی۔ [۲۷][۲۸] آخر کار سربیا اک خود مختار ملک بن گیا تے بوہتے مسلماناں نوں کڈ دتا گیا۔ [۲۹] بغاوتاں دے دوران ۱۵٬۰۰۰-۲۰٬۰۰۰ مسلمان بھج گئے یا کڈ دتے گئے۔ [۳۰] بلغراد تے باقی سربیا وچ ۲۳٬۰۰۰ دے نیڑے مسلماناں دی آبادی رہ گئی جنہاں نوں ۱۸۶۲ دے بعد کلیمگدان دے نیڑے عثمانی فوجیاں دے ذریعہ سربیائی شہریاں دے قتل عام دے بعد زبردستی بے دخل کر دتا گیا۔ [۲۸][۳۱] اس دے بعد کچھ مسلمان خاندان بوسنیا وچ ہجرت کر کے دوبارہ آباد ہوئے، جتھے انہاں دی اولاداں اج شہری مراکز جداں شاماتس ، تزلہ ، فوچا تے سوائیوو وچ رہائش پذیر نيں۔ [۳۲][۳۳]

یونانی انقلاب

سودھو۱۸۲۱ وچ ، جنوبی یونان وچ اک وڈی یونانی بغاوت پھوٹ پئی۔ باغیاں نے بوہتے پینڈو علاقےآں اُتے کنٹرول حاصل کر ليا جدوں کہ مسلماناں تے یہودیاں نے اپنے آپ نوں قلعہ بند قصبےآں تے قلعےآں وچ پناہ دتی۔ [۳۴] انہاں وچوں ہر اک دا محاصرہ کيتا گیا تے آہستہ آہستہ فاقہ کشی یا ہتھیار سُٹن دے ذریعے بوہتے یونانیاں نے اپنے قبضے وچ لے لیا۔ اپریل ۱۸۲۱ دے قتل عام وچ تقریباً ۱۵۰۰۰ مارے گئے۔ [۳۴] بدترین قتل عام طرابلس وچ ہويا، تقریباً ۸۰۰۰ مسلمان تے یہودی مارے گئے۔ [۳۴] اس دے جواب وچ ، قسطنطنیہ، سمرنا ، قبرص تے ہور جگہاں اُتے یونانیاں دے خلاف وڈے پیمانے اُتے انتقامی کارروائیاں ہوئیاں؛ ہزاراں مارے گئے تے عثمانی سلطان نے سلطنت وچ تمام یونانیاں نوں مکمل طور اُتے ختم کرنے دی پالیسی اُتے غور کيتا۔ [۳۵] آخر کار اک آزاد یونان قائم ہويا۔ اس دے علاقے دے بوہتے مسلمان لڑائی دے دوران مارے گئے یا بے دخل کر دتے گئے۔ [۳۴] برطانوی مؤرخ ولیم سینٹ کلیئر دا استدلال اے کہ جسنوں اوہ "نسل کشی دا عمل" کہندے نيں، اودوں ختم ہويا جدوں آزاد یونان بننے دے لئی قتل کرنے دے لئی ہور ترک نئيں سن ۔ [۳۵]

بلغاریہ دی بغاوت

سودھو۱۸۷۶ وچ بلغاریہ وچ درجناں دیہاتاں وچ بغاوت پھوٹ پئی۔ پہلے حملے مقامی مسلماناں دے خلاف کيتے گئے [۳۶] لیکن تھوڑے ہی عرصے وچ عثمانیاں نے اس بغاوت نوں پرتشدد طریقے توں کچل دتا۔

۱۸۷۶ توں ۱۹۸۹ تک، بلغاریہ ( ترک ، تاتار ، پومکس تے مسلم روما ) توں مسلماناں نوں ترکی توں کڈ دتا گیا؛ جداں کہ روس-ترک جنگ (۱۸۷۷–۱۸۷۸) دے دوران، بلقان دیاں جنگاں (۱۹۱۲–۱۹۱۳)، تے ۱۹۸۹ وچ بلغاریہ توں ترکاں دا اخراج ۔ [۱]

روس ترک جنگ

سودھوبلغاریہ

سودھوبلغاریہ دی بغاوت بالآخر روس تے عثمانیاں دے درمیان جنگ دا باعث بنی۔ روس نے دوبردوزہ تے شمالی بلغاریہ دے ذریعے عثمانی بلقان اُتے حملہ کرکے مسلم آبادی اُتے حملہ کيتا۔ اس جنگ وچ عثمانیاں نوں شکست ہوئی تے اس عمل وچ بلغاریہ دے تقریباً نصف مسلمان قسطنطنیہ تے اناطولیہ دی طرف بھج گئے۔ ایہ سخت سردی سی تے انہاں دا اک وڈا حصہ مر گیا۔ انہاں وچوں کچھ جنگ دے بعد واپس آگئے لیکن انہاں وچوں اکثر واپس چلے گئے۔ بلغاریائی مسلمان (ان دا اک حصہ ترک) بوہتے بحیرہ مرمرہ دے آس پاس آباد سن ۔ انہاں وچوں کچھ دولت مند سن تے انہاں نے بعد دے سالاں وچ عثمانی اشرافیہ وچ اہم کردار ادا کيتا۔ جنگ توں پہلے بلغاریہ دی ۱٫۵ ملین مسلم آبادی دا تقریباً نصف ختم ہو چکيا سی، اک اندازے دے مطابق ۲۰۰٬۰۰۰ ہلاک ہو گئے تے باقی بھج گئے۔ [۳۷]

امن دے زمانے وچ ہجرت جاری رہی، ۱۸۸۰ تے ۱۹۱۱ دے درمیان تقریباً ۳۵۰٬۰۰۰ بلغاریائی مسلماناں نے ملک چھڈ [۳۸] ۔

سربیا-عثمانی جنگ (۱۸۷۶–۷۸)

سودھو۱۸۷۷ وچ سربیا تے سلطنت عثمانیہ دے درمیان دشمنی دے دوسرے دور دے شروع ہوݨ دے موقع پر، نیش، پیروٹ، ورانجے، لیسکوواک، پروکوپلجے تے کرشملیجا دے ضلعے وچ اک قابل ذکر مسلم آبادی موجود سی۔ [۳۹] ٹوپلیکا ، کوسانیکا ، پستا ریکا تے جابلانیکا دی وادیاں دے پینڈو حصے تے اس توں ملحقہ نیم پہاڑی اندرونی حصے وچ مسلم البانیائی آبادی آباد سی جداں کہ انہاں علاقےآں وچ سرب دریا دے منہ تے پہاڑی ڈھلواناں دے نیڑے رہندے سن تے دونے لوک جنوبی موراوا ندی دے دوسرے علاقےآں وچ آباد سن ۔ بیسن [۴۰] [۴۱] بوہتے علاقے دی مسلم آبادی گھیگ البانوی نسلی تے شہری مراکز وچ آباد ترکاں اُتے مشتمل سی۔ [۴۲] ترکاں دا کچھ حصہ البانوی نژاد سی۔ [۴۳] نیش تے پیروت دے شہراں وچ مسلمان ترکی بولنے والے سن ۔ وارنويں تے لیسکوواتس ترکی تے البانی بولنے والے سن ۔ پروکوپلئی تے کورشملیا البانی بولنے والے سن ۔ [۴۲] 1860 دی دہائی دے دوران عثمانیاں دے ذریعہ نیش دے ماحول دے آس پاس اودوں دی سرحد دے نیڑے سرکیسیائی مہاجرین دی اک اقلیت وی سی۔ [۴۴] انہاں علاقےآں وچ جنگ دے موقع اُتے مسلماناں دی آبادی دے حجم دے لحاظ توں اندازے وکھ وکھ ہُندے نيں جنہاں دی تعداد ۲۰۰٬۰۰۰ توں لے کے ۱۳۱٬۰۰۰ تک کم اے۔ [۴۵][۴۶][۴۷] ۶۰-۷۰٬۰۰۰ توں گھٹ توں گھٹ ۳۰٬۰۰۰ تک جنگ دی وجہ توں سلطنت عثمانیہ دے لئی خطہ چھڈݨ والے مسلمان پناہ گزیناں دی تعداد دے بارے وچ اندازہ لگایا گیا اے۔ [۴۸][۴۹][۵۰][۵۱][۵۲][۵۳] انہاں علاقےآں توں البانوی آبادی دی روانگی اس انداز وچ کيتی گئی سی کہ اج اسنوں نسلی صفائی دے طور اُتے بیان کيتا جائے گا۔ [۵۴]

سربیا تے عثمانی افواج دے درمیان دشمنی ۱۵ دسمبر ۱۸۷۷ نوں سربیا توں روس-ترک جنگ وچ داخل ہوݨ دی روسی درخواست دے بعد شروع ہوئی۔ [۵۵] سربیا دی فوج دے دو مقاصد سن : نیش اُتے قبضہ کرنا تے نیش-صوفیہ عثمانی مواصلاتی لائناں نوں توڑنا۔ [۵۶] سربیا دی افواج وسیع تر ٹوپلیکا تے موراوا وادیاں وچ داخل ہوئیاں تے شہری مراکز جداں نیش، کورشملیا، پروکوپلئی، لیسکوواتس، تے وارنويںاور انہاں دے آس پاس دے پینڈو تے پہاڑی ضلعے اُتے قبضہ کر ليا۔ [۵۷] انہاں خطےآں وچ ، البانیہ دی آبادی جس علاقے وچ اوہ مقیم سن اس اُتے انحصار کردے ہوئے مویشی، جائیداد تے ہور سامان چھڈ کے قریبی پہاڑاں وچ بھج گئے سن ۔ [۵۸] کچھ البانی واپس آئے تے سربیا دے حکام دے حوالے کے دتے، جدوں کہ ہور نے اپنی پرواز جنوب دی طرف عثمانی کوسوو دی طرف جاری رکھی۔ [۵۹] سربیا دی افواج نوں بعض علاقےآں وچ البانوی مزاحمت دا وی سامنا کرنا پيا جس نے انہاں علاقےآں وچ انہاں دی پیش قدمی نوں سست کر دتا جس دے نتیجے وچ اک اک کر کے دیہات اُتے قبضہ کرنا پيا جو خالی ہو گئے۔ [۶۰] اک چھوٹی البانی آبادی میدویدا دے علاقے وچ رہی، جتھے انہاں دی اولاداں اج وی مقیم نيں۔ [۶۱] انہاں پناہ گزیناں دی عثمانی کوسوو دی طرف پسپائی نوں گولجک پہاڑاں اُتے روک دتا گیا جدوں جنگ بندی دا اعلان کيتا گیا۔ [۶۰] البانوی آبادی نوں نويں عثمانی سربیائی سرحد دے نال نال لیب دے علاقے تے شمالی کوسوو دے ہور حصےآں وچ دوبارہ آباد کيتا گیا۔ [۶۲] [۶۳][۶۴] بوہتے البانیائی پناہ گزیناں نوں وسطی تے جنوب مشرقی کوسوو دی ۳۰ توں ودھ وڈی پینڈو بستیاں تے شہری مراکز وچ دوبارہ آباد کيتا گیا جس توں انہاں دی آبادی وچ خاطر خواہ وادھا ہويا۔ [۶۲] [۴۷][۶۵] البانیائی پناہ گزیناں تے مقامی کوسوو البانیاں دے درمیان وسائل دے حوالے توں تناؤ پیدا ہويا، کیونجے سلطنت عثمانیہ نوں انہاں دی ضروریات تے معمولی حالات نوں پورا کرنا مشکل سی۔ [۶۶] مقامی کوسوو سرباں اُتے آنے والے البانوی پناہ گزیناں دی وجہ توں انتقامی حملےآں دی صورت وچ تناؤ وی پیدا ہويا جس نے آنے والی دہائیاں وچ جاری سربیائی-البانی تنازعہ دے آغاز وچ اہم کردار ادا کيتا۔ [۵۴][۶۶][۶۷]

بوسنیا

سودھو۱۸۷۵ وچ بوسنیا وچ مسلماناں تے عیسائیاں دے درمیان لڑائی چھڑ گئی۔ ۱۸۷۸ دی برلن کانگریس وچ سلطنت عثمانیہ دے معاہدے اُتے بعد بوسنیا اُتے آسٹریا ہنگری دا قبضہ ہو گیا۔ [۶۸] بوسنیائی مسلماناں (بوسنیاکس) نے اسنوں عثمانیاں دی طرف توں غداری سمجھیا تے اپنے طور اُتے چھڈ دتا، محسوس کيتا کہ اوہ اپنے وطن دا دفاع کر رہے نيں نہ کہ وسیع سلطنت کا۔ [۶۸] ۹ جولائی توں ۲۰ اکتوبر ۱۸۷۸ تک یا تقریباً تن ماہ تک، بوسنیائی مسلماناں نے تقریباً سٹھ فوجی مصروفیات وچ آسٹرو ہنگری افواج دے خلاف مزاحمت دی جس وچ ۵۰۰۰ افراد زخمی ہوئے یا ہلاک ہوئے۔ [۶۸] کچھ بوسنیائی مسلماناں نے نويں غیر مسلم انتظامیہ دے تحت اپنے مستقبل تے صحت دے بارے وچ فکر مند، بوسنیا نوں سلطنت عثمانیہ دے لئی چھڈ دتا۔ [۶۸] ۱۸۷۸ توں ۱۹۱۸ تک، 130,000 [۶۹] تے ۱۵۰٬۰۰۰ دے درمیان بوسنیائی مسلماناں نے بوسنیا توں عثمانیاں دے زیر کنٹرول علاقےآں، کچھ بلقان ، باقی اناطولیہ ، لیونٹ تے مغرب دی طرف روانہ ہوئے۔ [۷۰] اج، عرب دنیا وچ ایہ بوسنیائی آبادیاں ضم ہو گئیاں نيں حالانکہ انہاں نے اپنی اصلیت دی یاداں برقرار رکھی ہوئیاں نيں تے کچھ بوزنیاک (عربی وچ بوشناک دے طور اُتے پیش کيتا جاندا اے ) نوں کنیت دے طور اُتے رکھدے نيں۔ [۷۱][۷۲]

چرکسیا

سودھوروس-جرکس جنگ چرکسیا تے روس دے درمیان ۱۰۱ سال طویل فوجی تنازعہ سی۔ [۷۳] چرکسیا سلطنت عثمانیہ دا اصل حصہ سی لیکن حقیقت وچ آزاد سی۔ تنازعہ ۱۷۶۳ وچ شروع ہويا، جدوں روسی سلطنت نے سرکاشیا دے علاقے وچ دشمنی قلعے قائم کرنے دی کوشش کيتی تے سرکاشیا نوں تیزی توں الحاق کرنے دی کوشش کيتی، جس دے بعد سرکاشیا نے الحاق توں انکار کر دتا۔ [۷۴] صرف ۱۰۱ سال بعد ختم ہويا جدوں ۲۱ مئی ۱۸۶۴ نوں سرکاسیا دی آخری مزاحمتی فوج نوں شکست ہوئی، جس توں ایہ روسی سلطنت دے لئی تھکا دینے والی تے جانی نقصان دے نال نال تریخ وچ روس دی ہن تک دی واحد طویل ترین جنگ سی۔ [۷۵]

جنگ دے اختتام اُتے سرکیسیائی نسل کشی ہوئی جس وچ امپیریل روس دا مقصد منظم طریقے توں سرکیسیائی لوکاں نوں تباہ کرنا سی [۷۶][۷۷][۷۸] جتھے روسی افواج نے کئی جنگی جرائم دا ارتکاب کيتا سی [۷۹] تے تقریباً ۱٫۵ ملین سرکیشین مارے گئے یا مشرق وسطیٰ خصوصاً جدید دور دے ترکی وچ بے دخل کر دتے گئے۔ [۷۳] گریگوری زاس جداں روسی جرنیلاں نے سرکیسیئن نوں "سب ہیومن گندگی" دے طور اُتے بیان کيتا تے سائنسی تجربات وچ انہاں دے قتل تے استعمال دا جواز پیش کيتا۔ [۸۰]

جنوبی قفقاز

سودھوکارس دے آس پاس دا علاقہ روس دے حوالے کے دتا گیا۔ اس دے نتیجے وچ مسلماناں دی اک وڈی تعداد اوتھے توں نکل کے باقی عثمانی سرزمیناں وچ آباد ہو گئی۔ باتم تے اس دے آس پاس دا علاقہ وی روس دے حوالے کے دتا گیا جس دی وجہ توں بوہت سارے مقامی جارجیائی مسلمان مغرب دی طرف ہجرت کر گئے۔ [۸۱] انہاں وچوں اکثر اناطولیہ دے بحیرہ اسود دے ساحل دے آس پاس آباد ہوئے۔

بلقان دیاں جنگاں

سودھو

۱۹۱۲ وچ سربیا، یونان، بلغاریہ تے مونٹی نیگرو نے عثمانیاں دے خلاف جنگ دا اعلان کيتا۔ عثمانیاں نے جلد ہی علاقہ کھو دتا۔ Geert-Hinrich Ahrens دے مطابق، "حملہ آور فوجاں تے عیسائی باغیاں نے مسلم آبادی اُتے وسیع پیمانے اُتے مظالم ڈھائے۔" [۸۲] کوسوو تے البانیہ وچ بوہتے متاثرین البانوی سن جدوں کہ ہور علاقےآں وچ بوہتے متاثرین ترک تے پومکس سن ۔ روڈوپس وچ پوماکس دی اک وڈی تعداد نوں زبردستی آرتھوڈوکس وچ تبدیل کيتا گیا لیکن بعد وچ انہاں نوں دوبارہ تبدیل ہوݨ دی اجازت دتی گئی، انہاں وچوں اکثر نے ایسا کيتا۔ [۸۳] اس جنگ دے دوران سیکڑاں ہزاراں ترک تے پومکس اپنے پنڈ چھڈ کے پناہ گزین بن گئے۔ بلقان جنگاں اُتے بین الاقوامی کمیشن دی رپورٹ وچ دسیا گیا اے کہ بوہت سارے ضلعے وچ مسلماناں دے دیہات نوں انہاں دے عیسائی پڑوسیاں نے منظم طریقے توں جلا دتا سی۔ اک برطانوی رپورٹ دے مطابق موناستیر وچ ۸۰ فیصد مسلماناں دے دیہات نوں سربیا تے یونانی فوج نے جلا دتا سی۔ گیانیتسا وچ جداں کہ یونانی فوج نے سالونیکا صوبے وچ مسلماناں دے بوہت سارے دیہاتاں دے نال مسلم کوارٹر نوں جلا دتا سی۔ یونانی تے بلغاریہ دی فوجاں دی طرف توں ترکاں دے خلاف قتل عام تے عصمت دری دی وی اطلاع اے۔ [۸۴] آرنلڈ ٹوئنبی انہاں مسلم پناہ گزیناں دی تعداد دسدے نيں جو ۱۹۱۲–۱۹۱۵ دے درمیان بلغاریہ، سربیا تے یونانی کنٹرول وچ آنے والے خطہ توں فرار ہو گئے سن جو ۲۹۷٬۹۱۸ سن ۔ [۸۵] جسٹن میکارتھی بلقان جنگاں (۱۹۱۲–۲۰) دے دوران تے اس دے بعد پناہ گزیناں دی تعداد ۴۱۳٬۹۲۲ دسدے نيں، تے ہور دسدے نيں کہ ۱۹۱۱–۱۹۲۶ دے درمیانی عرصے وچ ۲٬۳۱۵٬۲۹۳ مسلماناں وچوں جو یورپ وچ سلطنت عثمانیہ توں لئی گئے علاقےآں وچ مقیم سن ۔ البانیہ نوں چھڈ کے)، ۸۱۲٬۷۷۱ ترکی وچ ختم ہوئے (جنہاں وچ یونان تے ترکی دے درمیان آبادی دا تبادلہ وی شامل اے )، ۶۳۲٬۴۰۸ مر گئے، تے ۸۷۰٬۱۱۴ باقی رہے۔ [۸۶] ۱۹۲۳ تک، ۱۹۱۲ دی صرف ۳۸ فیصد مسلم آبادی ہن وی بلقان وچ رہندی سی۔ ایمری ایرول دے مطابق، ۴۱۰٬۰۰۰ مسلمان سلطنت عثمانیہ وچ بے گھر ہوئے تے ۱۰۰٬۰۰۰ توں ودھ انہاں دی پرواز دے دوران ہلاک ہوئے۔ [۸۷] سلونیکا ( تھیسالونیکی ) تے ایڈریانوپل ( ایڈیرنے ) انہاں دے نال بھرے ہوئے سن ۔ سمندری تے زمینی راستے توں اوہ بوہتے عثمانی تھریس تے اناطولیہ وچ آباد ہوئے۔

پہلی جنگ عظیم تے ترکی دی جنگ آزادی

سودھوقفقاز مہم

سودھوتریخ دان اوغور امت اونگور نے نوٹ کيتا کہ عثمانی سرزمین اُتے روسی حملے دے دوران، "روسی فوج تے آرمینیائی رضاکاراں دی طرف توں مقامی ترکاں تے کرداں دے خلاف بوہت سارے مظالم ڈھائے گئے۔" [۸۸] جنرل لیابھَو نے کسی وی ترک نوں دیکھدے ہی قتل کرنے تے مسجد نوں تباہ کرنے دا حکم دتا۔ [۸۹][۹۰] بورس شاخووسکوئی دے مطابق آرمینیائی قوم پرست مقبوضہ علاقےآں وچ مسلماناں نوں ختم کرنا چاہندے سن ۔ [۹۱] مقامی مسلمان ترکاں تے کرداں دا اک وڈا حصہ ۱۹۱۴–۱۹۱۸ دے روسی حملے دے بعد مغرب توں بھج گیا، طلعت پاشا دی نوٹ بک وچ دتی گئی تعداد ۷۰۲٬۹۰۵ ترک اے۔ رومیݪ دا تخمینہ اے کہ ۱۲۸٬۰۰۰-۶۰۰٬۰۰۰ مسلمان ترک تے کرد روسی فوجیاں تے آرمینیائی بے قاعدہاں دے ہتھوں مارے گئے۔ ترک شماریات دان احمد ایمن یلمان دے مطابق انہاں وچوں گھٹ توں گھٹ ۱۲۸٬۰۰۰ ۱۹۱۴–۱۹۱۵ دے درمیان سن ۔ [۹۲] ۱۹۱۷ وچ عارضی حکومت دے قیام دے بعد، تقریباً ۳۰٬۰۰۰-۴۰٬۰۰۰ مسلماناں نوں بدلہ دے طور اُتے فاسد آرمینیائی اکائیاں دے ذریعے قتل کر دتا گیا۔ [۹۲] ترک-جرمن تریخ دان تانیر اکم نے کتاب A Shameful Act وچ وہپ پاشا دی طرف توں ۱۹۱۷–۱۹۱۸ وچ مغربی آرمینیا توں آرمینیائی تے روسی افواج دی پسپائی دے دوران مسلماناں دے خلاف انتقامی کارروائیاں دے تفصیلی بیان دے بارے وچ لکھیا اے، جس وچ ارزنکن تے بےبرٹ دے علاقےآں وچ ہلاکتاں دی تعداد ۳٬۰۰۰ سی۔ . اک ہور عینی شاہد دی گواہی دی تحریر وی جس وچ دعویٰ کيتا گیا سی کہ ایرزورم دے علاقے وچ ۳٬۰۰۰ ہلاک ہوئے، [۹۳] تے ۱۹۱۸ دے موسم بہار وچ کارس وچ ۲۰٬۰۰۰ ہلاک ہوئے۔ اکم نے ارزورم دے ولایت دے مطالعہ دا وی ذکر کيتا اے جس وچ ۱۹۱۸ دے موسم بہار وچ قتل عام مسلماناں دی تعداد ۲۵٬۰۰۰ دسی گئی اے، پر، آرمینیائی مورخ وہاکن دادریان دا امتحان پیش کردے نيں جو عثمانی تیسری فوج دے جنگ دے وقت دے ریکارڈ توں دعویٰ کردے نيں کہ " مجموعی طور اُتے تقریباً ۵٬۰۰۰-۵٬۵۰۰ متاثرین ملوث نيں۔" اکم نے اک ترک ماخذ دے بارے وچ لکھیا اے جس وچ کارس وچ ۱۹۱۹ دے سیاݪ تے بہار دے دوران مسلماناں دی ہلاکتاں دی تعداد ۶٬۵۰۰ دسی گئی اے، جداں کہ ۲۲ مارچ ۱۹۲۰ نوں کاظم کارابکیر نے کارس دے بعض دیہاتاں تے علاقےآں وچ ایہ تعداد ۲٬۰۰۰ دسی سی۔ [۹۴] حلیل بے نے ۱۹۱۹ وچ کارابکیر نوں لکھے اک خط وچ دعویٰ کيتا کہ ایغدیر دے ۲۴ پنڈ مسمار دے دتے گئے نيں۔ [۹۵]

فرانکو ترک جنگ

سودھوCilicia اُتے پہلی جنگ عظیم دے بعد انگریزاں نے قبضہ کر ليا سی، جنہاں نوں بعد وچ فرانسیسیاں نے تبدیل کر دتا سی۔ فرانسیسی آرمینیائی لشکر نے آرمینیائی نسل کشی دے شکار آرمینیائی پناہ گزیناں نوں خطے وچ مسلح کيتا تے انہاں دی مدد کيتی۔ بالآخر ترکاں نے فرانسیسی قبضے دے خلاف مزاحمت دا جواب دتا، ماراش، عنتاب تے عرفہ وچ لڑائیاں ہوئیاں ۔ انہاں وچوں بوہتے شہر اس عمل دے دوران تباہ ہو گئے سن جنہاں وچ شہریاں نوں شدید مشکلات دا سامنا کرنا پيا سی۔ ماراش وچ ، ۴٫۵۰۰ ترک ہلاک ہوئے۔ [۹۶] فرانسیسیاں نے ۱۹۲۰ دے بعد آرمینیائی باشندےآں دے نال مل کے علاقہ چھڈ دتا۔ آرمینیائی نسل کشی دا بدلہ مسلح آرمینیائیاں دے لئی جواز دے طور اُتے کم کيتا۔ [۹۷]

اس دے علاوہ فرانکو-ترک جنگ دے دوران، Kaç Kaç دا واقعہ پیش آیا، جس دا حوالہ ۲۰ جولائی ۱۹۲۰ دے فرانکو-آرمینی آپریشن دی وجہ توں اڈانا شہر توں ہور پہاڑی علاقےآں وچ ۴۰٬۰۰۰ ترکاں دے فرار دا اے۔ فرار دے دوران، فرانسیسی آرمینیائی طیارےآں نے فرار ہوݨ والی آبادی تے بیلیمیڈک ہسپتال اُتے بمباری کيتی۔

گریکو-ترکی جنگ

سودھو

یونانی لینڈنگ تے گریکو-ترک جنگ (۱۹۱۹–۱۹۲۲) دے دوران مغربی اناطولیہ اُتے قبضے دے بعد، ترک مزاحمتی سرگرمیاں دا جواب مقامی مسلماناں دے خلاف دہشت گردی توں دتا گیا۔ یونانی فوج دے پیش قدمی دے نال ہی قتل، عصمت دری تے پنڈ جلانے دے واقعات رونما ہوئے۔ [۹۹] پر، جداں کہ اودوں دی اک برطانوی انٹیلی جنس رپورٹ وچ دسیا گیا اے، عام طور اُتے "مقبوضہ علاقے دے باشندےآں نے بوہتے صورتاں وچ یونانی حکومت دی آمد نوں بغیر کسی ہچکچاہٹ دے قبول کيتا اے تے بعض صورتاں وچ بلاشبہ اسنوں [ترک] قوم پرستاں اُتے ترجیح دتی اے۔ ایسا لگدا اے کہ حکومت دی نیہہ دہشت گردی اُتے رکھی گئی اے۔" برطانوی فوجی اہلکاراں نے مشاہدہ کيتا کہ یوسک دے نیڑے یونانی فوج دا مسلم آبادی نے "[ترک] قوم پرست فوجیاں دے لائسنس تے جبر توں آزاد ہوݨ" اُتے گرمجوشی توں خیر مقدم کیا؛ یونانی فوجیاں دی طرف توں مسلم آبادی دے خلاف "کدی کدائيں بدتمیزی دے واقعات" ہُندے سن، تے مجرماں اُتے یونانی حکام دی طرف توں مقدمہ چلایا جاندا سی، جداں کہ "بدترین شرپسند" "یونانی فوج دے ذریعے بھرتی کيتے گئے رُگ آرمینیائی" سن، جنہاں نوں پھرواپس قسطنطنیہ بھیج دتا گیا سی۔ [۱۰۰]

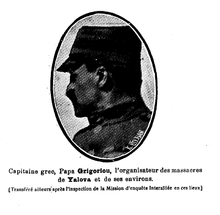

یونانی قبضے دے دوران، یونانی فوجیاں تے مقامی یونانیاں، آرمینیائی، تے سرکیسیائی گروہاں نے ۱۹۲۱ دے اوائل وچ مقامی مسلم آبادی دے خلاف یالووا جزیرہ نما قتل عام دا ارتکاب کيتا۔ [۱۰۱] اس دے نتیجے وچ ، بعض ذرائع دے مطابق، سی دی اموات وچ ۔ ۳۰۰ مقامی مسلم آبادی دے نال نالت۔ ۲۷ پنڈ۔ [۱۰۲] ہلاک ہوݨ والےآں دی صحیح تعداد معلوم نئيں اے۔ عثمانی عہدیدار دے جمع کردہ بیانات، ہلاکتاں دی نسبتاً کم تعداد نوں ظاہر کردے نيں: عثمانی انکوائری دی نیہہ اُتے جس اُتے ۱۷۷ زندہ بچ جانے والےآں نے جواب دتا، صرف ۳۵ نوں ہلاک، زخمی یا ماریا پیٹا گیا یا لاپتہ دسیا گیا۔ ایہ ٹوئنبی دے اکاؤنٹس دے مطابق وی اے کہ اک توں دو قتل آبادی نوں بھگانے دے لئی کافی سن ۔ [۱۰۳] اک ہور ذریعہ دا اندازہ اے کہ ۷٬۰۰۰ وچوں بمشکل ۱٫۵۰۰ مسلمان یالووا دے ماحول وچ زندہ بچ سکے۔ [۱۰۴]

یونانیاں نے وسطی اناطولیہ تک تمام راستے اگے بڑھائے۔ ۱۹۲۲ وچ ترکی دے حملے دے بعد یونانی پِچھے ہٹ گئے تے نارمن ایم نائمارک نے نوٹ کيتا کہ "یونانی پسپائی مقامی آبادی دے لئی قبضے توں وی ودھ تباہ کن سی"۔ [۱۰۵] پسپائی دے دوران، قصبےآں تے دیہاتاں نوں اک جھلسی ہوئی زمین دی پالیسی دے اک حصے دے طور اُتے جلا دتا گیا، اس دے نال قتل عام تے عصمت دری کيتی گئی۔ اس جنگ دے دوران، مغربی اناطولیہ دا اک حصہ تباہ ہو گیا، وڈے قصبے جداں مانیسا ، صالحی تے بوہت سارے دیہات جلا دتے گئے۔ [۱۰۶] الاشیہر وچ ۳۰۰۰ مکانات۔ [۱۰۷] برطانوی، فرانسیسی، امریکی تے اطالوی افسراں اُتے مشتمل بین الائیڈ کمیشن نے پایا کہ "ترک دیہاتاں نوں تباہ کرنے تے مسلماناں دی آبادی نوں ختم کرنے دا اک منظم منصوبہ اے۔" [۱۰۸] مارجوری ہاؤسپیئن دے مطابق، یونانی قبضے دے تحت ازمیر وچ ۴۰۰۰ مسلماناں نوں پھانسی دتی گئی۔ [۱۰۹]

جنگ دے دوران، مشرقی تھریس وچ (جو معاہدہ Sèvres دے نال یونان دے حوالے کيتا گیا سی)، تقریباً ۹۰٬۰۰۰ ترک دیہاتی یونانیاں توں بلغاریہ تے استنبول بھج گئے۔

جنگ دے بعد، یونان تے ترکی دے درمیان امن مذاکرات ۱۹۲۲–۱۹۲۳ دی لوزان کانفرنس توں شروع ہوئے۔ کانفرنس وچ ترک وفد دے چیف مذاکرات کار عصمت پاشا نے ۱٫۵ ملین اناطولیائی ترکاں دا تخمینہ پیش کيتا جو یونانی قبضے دے علاقے وچ جلاوطن یا مر گئے سن ۔ انہاں وچوں، McCarthy دا اندازہ اے کہ ۸۶۰٬۰۰۰ بھج گئے تے ۶۴۰٬۰۰۰ مر گئے۔ بوہت سارے لوکاں دے نال، جے مرنے والےآں وچوں بوہتے نئيں تاں پناہ گزین ہوݨ دے ناطے بھی۔ مردم شماری دے اعداد و شمار دا موازنہ ظاہر کردا اے کہ ۱٬۲۴۶٬۰۶۸ اناطولیہ دے مسلمان پناہ گزین بن چکے سن یا مر چکے سن ۔ ہور برآں، عصمت پاشا نے یونانی قبضے دے علاقے وچ ۱۴۱٬۸۷۴ عمارتاں دی تباہی تے ۳٬۲۹۱٬۳۳۵ فارم جانوراں دے ذبح یا چوری دے اعدادوشمار شیئر کيتے نيں۔ [۱۱۰]سانچہ:Better source یونان تے ترکی دی جنگ دے بعد جو امن ہويا اس دے نتیجے وچ یونان تے ترکی دے درمیان آبادی دا تبادلہ ہويا ۔ نتیجے دے طور پر، یونان دی مسلم آبادی، مغربی تھریس نوں چھڈ کے، تے جزوی طور پر، مسلم چام البانیائی ، [۱۱۱] نوں ترکی منتقل کر دتا گیا۔ [۱۱۲]

کل ہلاکتاں

سودھوسلطنت عثمانیہ دے علاقائی سکڑاؤ دے دور وچ بلقان توں مسلماناں دی زبردستی نقل مکانی ۲۱ويں صدی وچ حالیہ علمی دلچسپی دا موضوع بنی اے۔

مرنے والےآں دی تعداد

سودھومؤرخ جسٹن میکارتھی دے مطابق، ۱۸۲۱–۱۹۲۲ دے درمیان، یونان دی جنگ آزادی دے آغاز توں لے کے سلطنت عثمانیہ دے خاتمے تک، ۵۰ لکھ مسلماناں نوں انہاں دی سرزمین توں کڈ دتا گیا تے ہور ۵۵ لکھ مارے گئے، انہاں وچوں کچھ جنگاں وچ مارے گئے، دوسرے بھکھ یا بیماری توں پناہ گزیناں دے طور اُتے ہلاک ہوئے۔ [۲] پر، McCarthy دے کم نوں بوہت سارے اسکالرز دی طرف توں سخت تنقید دا سامنا کرنا پيا اے جنہاں نے انہاں دے خیالات نوں ترکی دی طرف غیر یقینی طور اُتے متعصبانہ قرار دتا اے [۱۱۳] تے آرمینیائی باشندےآں دے خلاف ترک مظالم دا دفاع کرنے دے نال نال نسل کشی توں انکار وچ ملوث نيں۔ [۱۱۴][۱۱۵][۱۱۶]

میسی گبنی دے مطابق انہاں صدیاں دے دوران کل مسلمان مہاجرین دی تعداد کئی ملین دسی جاندی اے۔ [۱۱۷] راجر اوون دا اندازہ اے کہ سلطنت عثمانیہ دی آخری دہائی (۱۹۱۲–۱۹۲۲) دے دوران جدوں بلقان دیاں جنگاں، پہلی جنگ عظیم تے آزادی دی جنگ ہوئی، جدید ترکی دے علاقے وچ تقریباً ۲۰ لکھ مسلمان، شہری تے فوجی، ہلاک ہوئے۔ [۱۱۸]

مہاجرین دی آباد کاری

سودھوعثمانی حکام تے خیراندی ادارےآں نے تارکین وطن نوں کچھ مدد فراہم دی تے بعض اوقات انہاں نوں مخصوص تھانواں اُتے آباد کيتا۔ ترکی وچ بلقان دے بوہتے مہاجرین مغربی ترکی تے تھریس وچ آباد ہوئے۔ کاکیشین، انہاں علاقےآں دے علاوہ وسطی اناطولیہ تے بحیرہ اسود دے ساحل دے آس پاس وی آباد ہوئے۔ مشرقی اناطولیہ کچھ سرکیسیئن تے کاراپاک دیہاتاں دے علاوہ بوہتے آباد نئيں سی۔ پناہ گزیناں دے ذریعہ مکمل طور اُتے نويں پنڈ وی قائم کيتے گئے سن، مثال دے طور اُتے غیر آباد جنگلاندی علاقےآں وچ ۔ ۱۹۲۴ دے تبادلے دے بوہت سارے لوک ایجین دے ساحل دے نال سابق یونانی دیہات وچ آباد سن ۔ ترکی توں باہر، سرکیسیائی باشندے حجاز ریلوے دے نال تے شام دے ساحل اُتے کچھ کریٹان مسلمان آباد سن ۔

علمی بحث

سودھومائیکل مان دے مطابق میک کارتھی نوں اکثر بلقان دے مسلماناں دی موت دے اعداد و شمار اُتے ہوݨ والی بحث وچ ترکی دی طرف توں اک اسکالر دے طور اُتے دیکھیا جاندا اے۔ [۱۱۹] پر مان دا کہنا اے کہ جے انہاں اعداد و شمار نوں "۵۰ فیصد تک کم کر دتا جائے تاں وی اوہ خوفناک ہو جاواں گے"۔ [۱۱۹] آرمینیائی نسل کشی دے بارے وچ بحث وچ ، میکارتھی نسل کشی دی تردید کردا اے تے اسنوں ترکی دے حامی معروف عالم دے طور اُتے سمجھیا جاندا اے۔ [۱۲۰][۱۲۱] میک کارتھی دے علمی ناقدین تسلیم کردے نيں کہ مسلم شہری ہلاکتاں تے پناہ گزیناں دی تعداد (۱۹ويں تے ۲۰ويں صدی دے اوائل) اُتے انہاں دی تحقیق نے اک قابل قدر نقطہ نظر سامنے لیایا اے، جسنوں پہلے عیسائی مغرب وچ نظرانداز کيتا گیا سی: کہ انہاں سالاں دے دوران لکھاں مسلمان تے یہودی وی متاثر ہوئے تے ہلاک ہوئے۔ [۱۲۲][۱۲۳] ڈونلڈ ڈبلیو بلیچر ، بھانويں ایہ تسلیم کردے ہوئے کہ میک کارتھی ترکی دے حامی نيں، اس دے باوجود مسلمان شہری ہلاکتاں تے پناہ گزیناں دی تعداد دے بارے وچ اپنے علمی مطالعہ نوں "اک ضروری اصلاحی" قرار دتا اے جس وچ مغرب دے تمام متاثرین دے عیسائی ہوݨ تے تمام مجرماں دے مسلمان ہوݨ دے ماڈل نوں چیلنج کيتا گیا اے۔ [۱۲۳]

مورخ مارک بیونڈیچ دا اندازہ اے کہ ۱۸۷۸–۱۹۱۲ تک ۲۰ لکھ مسلماناں نے بلقان نوں اپنی مرضی توں یا غیر ارادی طور اُتے چھڈیا جدوں کہ ۱۹۱۲–۱۹۲۳ دے دوران بلقان وچ مسلماناں دی ہلاکتاں ہلاک تے بے دخل کيتے جانے والےآں دے تناظر وچ تقریباً ۳۰ لکھ توں تجاوز کر گئياں۔ [۱۲۴]

مسلماناں دے ورثے دی تباہی۔

سودھوظلم و ستم دے دوران مسلم ورثے نوں وڈے پیمانے اُتے نشانہ بنایا گیا۔ اپنی طویل حکمرانی دے دوران عثمانیاں نے بے شمار مسیتاں ، مدرسے ، کاروان سرائے ، حمام گاہاں تے ہور قسماں دی عمارتاں تعمیر کیتیاں۔ موجودہ تحقیق دے مطابق، تمام سائز دی تقریباً ۲۰٬۰۰۰ عمارتاں سرکاری عثمانی رجسٹراں وچ درج دی گئیاں نيں۔ [۱۲۵] پر بوہتے بلقان ملکاں وچ اس عثمانی ورثے دی بوہت گھٹ بچیاں نيں۔ [۱۲۶] بلقان دی عثمانی دور دی بوہتے مسیتاں تباہ ہو چکیاں نيں۔ جو ہن وی کھڑے نيں اکثر انہاں دے مینار تباہ ہو چکے سن ۔ ہیبسبرگ دی فتح توں پہلے، اوسیجیک وچ ۸-۱۰ مسیتاں سی، جنہاں وچوں کوئی وی اج باقی نئيں اے۔ [۱۲۷] بلقان دیاں جنگاں دے دوران بے حرمتی، مسیتاں تے مسلماناں دے قبرستاناں نوں تباہ کرنے دے واقعات ہوئے۔ [۱۲۷] ۱۷ويں صدی وچ عثمانی بلقان وچ ۱۶۶ مدارس وچوں صرف اٹھ باقی نيں تے انہاں وچوں پنج ایڈرن دے نیڑے نيں۔ [۱۲۵] اک اندازے دے مطابق ۹۵-۹۸٪ تباہ ہو چکے نيں۔ [۱۲۵] ایہی دوسری قسم دی عمارتاں دے لئی وی درست اے، جداں کہ مارکیٹ ہالز، کاروانسرائے تے حمام۔ [۱۲۵] بلقان دے پار کاروانسیریز دی اک سنگݪ توں صرف اک محفوظ اے جدوں کہ چار ہور دے مبہم کھنڈرات نيں۔ [۱۲۵] ۱۵۲۱ وچ نیگروپونٹے دے علاقے وچ ۳۴ وڈی تے چھوٹی مسیتاں، چھ حمام، دس اسکول تے ۶ درویش کنونٹس سن ۔ اج صرف اک حمام دی بربادی باقی اے۔ [۱۲۵]

| شہر | عثمانی دور حکومت وچ | ابھ تک اے۔ |

|---|---|---|

| شومین | ۴۰ | ۳ |

| سیرس | ۶۰ | ۳ |

| بلغراد | >۱۰۰ | ۱ |

| صوفیہ | >۱۰۰ | ۱ |

| Ruse | ۳۶ | ۱ |

| سرمسکا میترووتسا [۱۲۸] | ۱۷ | ۰ |

| اوسیجیک [۱۲۹] | ۷ | ۰ |

| پوژیگا [۱۳۰] | ۱۴-۱۵ | ۰ |

يادگار

سودھوترکی وچ انہاں واقعات توں متعلق ادب موجود اے، لیکن ترکی توں باہر، ایہ واقعات وڈی حد تک عالمی عوام دے لئی نامعلوم نيں۔

یورپ اُتے اثرات

سودھومارک لیوین دے مطابق، ۱۸۷۰ دی دہائی وچ وکٹورین عوام نے مسلماناں دے قتل عام تے بے دخلی دے مقابلے وچ عیسائیاں دے قتل عام تے بے دخلی اُتے بہت ودھ توجہ دتی، خواہ اس توں ودھ پیمانے اُتے ہوݨ۔ انہاں دا ہور کہنا اے کہ اس طرح دے قتل عام نوں بعض حلفےآں نے وی پسند کيتا۔ مارک لیوین نے ایہ وی دلیل دتی کہ غالب طاقتاں نے برلن دی کانگریس وچ "قومی اعدادوشمار" دی حمایت کردے ہوئے، "بلقان دی قومی تعمیر دے بنیادی آلے" نوں قانونی حیثیت دی: نسلی صفائی ۔ [۱۳۱]

یادگاراں

سودھو

اغدیر ، ترکی وچ اک يادگار اے جسنوں اغدیر نسل کشی دی يادگار تے میوزیم کہیا جاندا اے، جو پہلی جنگ عظیم دے مسلمان متاثرین دی ياد وچ ۔

۲۱ مئی ۲۰۱۲ نوں اناکلیا ، جارجیا وچ اک يادگار تعمیر کيتی گئی سی تاکہ چرکساں نوں کڈے جانے دی يادگار ہوئے۔ [۱۳۲]

مورتاں

سودھو-

1923 وچ آبادی دے تبادلے دے بعد کریٹن مسلم خاندان نوں ترکی بھیجیا گیا۔

-

Yeşilyayla, Erzurum دے قصبے وچ اک اجتماعی قبر دی کھدائی۔

وی دیکھو

سودھو- ترک عوام دے قتل عام دی لسٹ

- بعد دی سلطنت عثمانیہ وچ عیسائیاں اُتے ظلم و ستم

- بعد دی عثمانی نسل کشی

نوٹس

سودھوحوالے

سودھو- ↑ ۱.۰ ۱.۱ Pekesen, Berna (7 مارچ 2012). "Expulsion and Emigration of the Muslims from the Balkans". in Berger, Lutz. Leibniz Institute of European History. http://ieg-ego.eu/en/threads/europe-on-the-road/forced-ethnic-migration/berna-pekesen-expulsion-and-emigration-of-the-muslims-from-the-balkans. Retrieved on 9 ستمبر 2022.

- ↑ ۲.۰ ۲.۱ McCarthy, Justin Death and Exile: The Ethnic Cleansing of Ottoman Muslims, 1821–1922, Darwin Press Incorporated, 1996, سانچہ:آئی ایس بی این, Chapter one, The land to be lost, p. 1

- ↑ Adam Jones. (2010).Genocide: A Comprehensive Introduction page 65 & 152. "Incorporating a global-comparative perspective on the genocide of the last half-millenium has enabled important advances in the understanding of events central to the genocide studies field – such as the process of Ottoman imperial dissolution, reciprocal genocidal killing (during the "Unweaving" in the Balkans)...The human toll of this "Great Unweaving," from Greece's independence war in the early nineteenth century to the final Balkan wars of 1912–1913, was enormous. Hundreds of thousands of Ottoman Muslims were massacred in the secessionist drive.."

- ↑ Norman Itzkowitz, Ottoman Empire and Islamic Tradition. University of Chicago Press, 2008, سانچہ:آئی ایس بی این, p. 12

- ↑ Conversion to Islam in the Balkans: Kisve Bahas ̧petitions and Ottoman Social Life, 1670–1730, Anton Minkov, BRILL, 2004, سانچہ:آئی ایس بی این.

- ↑ The Geography of the Middle East, Stephen Hemsley Longrigg, James P. Jankowski, Transaction Publishers, 2009, سانچہ:آئی ایس بی این, p. 113.

- ↑ Hall, Richard C. (2002), The Balkan Wars, 1912–1913: prelude to the First World War, Routledge, pp. 136–137

- ↑ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Citation/CS1/COinS' not found.

- ↑ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Citation/CS1/COinS' not found.

- ↑ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Citation/CS1/COinS' not found.

- ↑ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Citation/CS1/COinS' not found.

- ↑ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Citation/CS1/COinS' not found.

- ↑ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Citation/CS1/COinS' not found.

- ↑ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Citation/CS1/COinS' not found.

- ↑ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Citation/CS1/COinS' not found.

- ↑ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Citation/CS1/COinS' not found.

- ↑ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Citation/CS1/COinS' not found.

- ↑ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Citation/CS1/COinS' not found.

- ↑ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Citation/CS1/COinS' not found.

- ↑ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Citation/CS1/COinS' not found.

- ↑ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Citation/CS1/COinS' not found.

- ↑ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Citation/CS1/COinS' not found.

- ↑ al-Arnaut, Muhamed Mufaku (1994). "Islam and Muslims in Bosnia 1878–1918: Two Hijras and Two Fatwās". Journal of Islamic Studies. 5. (2): 245–246. "This being the case, the Muslim Bosnians could no longer imagine any existence for Muslims outside the devlet unless they lived outside the pale of the din, it cannot be denied that the attitude of neighbouring countries had influenced this state of mind. For after two centuries of stability and supremacy dār ar-Islām was no longer immune from attack. Muslims now faced a new, unexpected, inconceivable situation. The triumph of their Christian enemies meant that, in order to survive, the Muslims had to choose either to Christianize and remain inside the Christian state or to emigrate southwards in order to remain Muslims within the Muslim state. Thus we notice that Austria in particular, when changing from the defensive to the offensive, was concentrating on Bosnia, but without its Muslims. in the war of 1737–9 we find Emperor Charles VI, in the edict addressed to the Muslim Bosnians dated جون 1737, outlining two options for them: 'whoever of them wishes to adopt Christianity, may be free to stay and retain his property, while those who do not may emigrate to wherever they want' They fared no better in the 1788–91 war, although Emperor Joseph I issued a proclamation in which he promised to respect Muslim rights and institutions. However, despite these pledges, the Muslims quickly disappeared from the areas ceded by the Ottoman Empire."

- ↑ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Citation/CS1/COinS' not found.

- ↑ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Citation/CS1/COinS' not found.

- ↑ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Citation/CS1/COinS' not found.

- ↑ Stefanović, Djordje (2005). "Seeing the Albanians through Serbian eyes: The Inventors of the Tradition of Intolerance and their Critics, 1804–1939." European History Quarterly. 35. (3): 466. "Extant class hatred of the Serbian peasants towards urban Muslim merchants and land owners was clearly a major motivator for mass violence. Nenadović describes the take-over of Valjevo by the rebels: At that time... there were twenty-four mosques and it was said that there were nearly three thousand Turkish and some two hundred Christian houses.... Any house that had not burnt, the Serbs tore to bits and took their windows and doors and everything else that could be removed."

- ↑ ۲۸.۰ ۲۸.۱ Palairet, Michael R (2003). The Balkan economiesت۔ 1800–1914: evolution without development. Cambridge University Press. p. 28-29. " As the characteristically high urbanization of Ottoman Europe reflected institutional structure rather than economic complexity, the dissolution of Ottoman institutions by the successor states could cause rapid deurbanization. This process occurred in its most striking form in Serbia. In the eighteenth century, Ottoman Serbia was highly urbanized, but during the wars and the revolutionary upheaval of 1789–1815, the Serbian towns experienced a precipitous decline. In 1777, there were reportedly some 6,000 houses in Belgrade," from which a population of 30,000 — 55,000 may be estimated. By about 1800, the town had shrunk to around 3,000 houses with 25,000 inhabitants, and in 1834 the number of houses had fallen further to 769. Late-eighteenth-century Užice had 2,900 Muslim houses; this indicates a population of around 20,000, for when the last 3,834 Muslims were driven from the town in 1862, they vacated 550 houses. Tihomir Dordević put the population of Užice in the late eighteenth century still higher, at 12,000 houses with about 60,000 inhabitants. By 1860, when Užice's population was 4,100, but still overwhelmingly Muslim, the effects of the town's decline were all too visible, the bazaars 'rotting and ruinous', and 'whole streets which stood here before the Servian revolution... turned into orchards'. In 1863, after the expulsions, there remained in the town a population of some 2,490. Valjevo in the 1770s was also a substantial place with 3,000 Muslim and 200 Christian houses. At least 5 other towns had 200 — 500 houses each. Given the low population density of Ottoman Serbia, a remarkably high proportion of its inhabitants were town dwellers. Belgrade pašaluk in the late eighteenth century had 376,000 Serbian and 40,000 — 50,000 Turkish inhabitants. On this basis, the two largest towns alone would have accounted for 11—27 per cent of the population of the pašaluk. The urban proportion could have been higher still, for a number of smaller towns dwindled into villages on the departure of the Ottomans.

- ↑ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Citation/CS1/COinS' not found.

- ↑ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Citation/CS1/COinS' not found.

- ↑ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Citation/CS1/COinS' not found.

- ↑ Zulfikarpašić, Adil (1998). The Bosniak. Hurst. p. 23-24. "In accordance with this principle Serbia had been cleansed of Muslims, and even of those Serbs who had converted to Islam and who lived around Užice and Valjevo. In negotiations between Turkey and Serbia they had been declared Turks and forced to move, and so they had resettled in Bosnia. There are still hundreds of families in Tuzla, Šamac, Sarajevo and Foča who are descendants of these immigrants from Užice — Serbian speaking Muslims. This was all a repeat of what had happened a few centuries before in Slavonia and Lika. The region of Lika, for example, was 65 per cent Muslim land until it fell into Austrian hands, when the Muslims were given the choice between expulsion and conversion."

- ↑ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Citation/CS1/COinS' not found.

- ↑ ۳۴.۰ ۳۴.۱ ۳۴.۲ ۳۴.۳ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Citation/CS1/COinS' not found.

- ↑ ۳۵.۰ ۳۵.۱ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Citation/CS1/COinS' not found.

- ↑ Jelavich, Barbara (1999), History of the Balkans: Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries, Vol. 1, Cambridge University Press, pp.347

- ↑ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Citation/CS1/COinS' not found.

- ↑ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Citation/CS1/COinS' not found.

- ↑ Jagodić, Miloš (1998). "The Emigration of Muslims from the New Serbian Regions 1877/1878". Balkanologie. 2 (2): para. 4, 9, 32–42, 45–61.

- ↑ Jagodić 1998, para. 4, 9, 32–42, 45–61.

- ↑ Luković, Miloš (2011). "Development of the Modern Serbian state and abolishment of Ottoman Agrarian relations in the 19th century" " Český lid. 98. (3): 298. "During the second war (دسمبر 1877 — جنوری 1878) the Muslim population fled towns (Vranya (Vranje), Leskovac, Ürgüp (Prokuplje), Niş (Niš), Şehirköy (Pirot), etc.) as well as rural settlements where they comprised ethnically compact communities (certain parts of Toplica, Jablanica, Pusta Reka, Masurica and other regions in the South Morava River basin). At the end of the war these Muslim refugees ended up in the region of Kosovo and Metohija, in the territory of the Ottoman Empire, following the demarcation of the new border with the Principality of Serbia. [38] [38] On Muslim refugees (muhaciri) from the regions of southeast Serbia, who relocated in Macedonia and Kosovo, see Trifunovski 1978, Radovanovič 2000."

- ↑ ۴۲.۰ ۴۲.۱ Jagodić 1998, para. 4, 5, 6.

- ↑ Jagodić 1998, para. 11.

- ↑ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Citation/CS1/COinS' not found.

- ↑ McCarthy, Justin (2000). "Muslims in Ottoman Europe: Population from 1800–1912". Nationalities Papers. 28. (1): 35.

- ↑ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Citation/CS1/COinS' not found.

- ↑ ۴۷.۰ ۴۷.۱ Sabit Uka (2004). Dëbimi i Shqiptarëve nga Sanxhaku i Nishit dhe vendosja e tyre në Kosovë:(1877/1878-1912)[The expulsion of the Albanians from Sanjak of Nish and their resettlement in Kosovo: (1877/1878-1912)]. Verana. pp. 26–29.

- ↑ Pllana, Emin (1985). "Les raisons de la manière de l'exode des refugies albanais du territoire du sandjak de Nish a Kosove (1878–1878) [The reasons for the manner of the exodus of Albanian refugees from the territory of the Sanjak of Nish to Kosovo (1878–1878)] ". Studia Albanica. 1: 189–190.

- ↑ Rizaj, Skënder (1981). "Nënte Dokumente angleze mbi Lidhjen Shqiptare të Prizrenit (1878–1880) [Nine English documents about the League of Prizren (1878–1880)]". Gjurmine Albanologjike (Seria e Shkencave Historike). 10: 198.

- ↑ Şimşir, Bilal N, (1968). Rumeli'den Türk göçleri. Emigrations turques des Balkans [Turkish emigrations from the Balkans]. Vol I. Belgeler-Documents. p. 737.

- ↑ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Citation/CS1/COinS' not found.

- ↑ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Citation/CS1/COinS' not found.

- ↑ Stefanović, Djordje (2005). "Seeing the Albanians through Serbian eyes: The Inventors of the Tradition of Intolerance and their Critics, 1804–1939." European History Quarterly. 35. (3): 470.

- ↑ ۵۴.۰ ۵۴.۱ Müller, Dietmar (2009). "Orientalism and Nation: Jews and Muslims as Alterity in Southeastern Europe in the Age of Nation-States, 1878–1941." East Central Europe. 36. (1): 70. "For Serbia the war of 1878, where the Serbians fought side by side with Russian and Romanian troops against the Ottoman Empire, and the Berlin Congress were of central importance, as in the Romanian case. The beginning of a new quality of the Serbian-Albanian history of conflict was marked by the expulsion of Albanian Muslims from Niš Sandžak which was part and parcel of the fighting (Clewing 2000 : 45ff.; Jagodić 1998 ; Pllana 1985). Driving out the Albanians from the annexed territory, now called "New Serbia," was a result of collaboration between regular troops and guerrilla forces, and it was done in a manner which can be characterized as ethnic cleansing, since the victims were not only the combatants, but also virtually any civilian regardless of their attitude towards the Serbians (Müller 2005b). The majority of the refugees settled in neighboring Kosovo where they shed their bitter feelings on the local Serbs and ousted some of them from merchant positions, thereby enlarging the area of Serbian-Albanian conflict and intensifying it."

- ↑ Jagodić 1998, para. 3, 17.

- ↑ Jagodić 1998, para. 17.

- ↑ Jagodić 1998, para. 17–26.

- ↑ Jagodić 1998, para. 18–20.

- ↑ Jagodić 1998, para. 18–20, 25.

- ↑ ۶۰.۰ ۶۰.۱ Jagodić 1998, para. 25.

- ↑ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Citation/CS1/COinS' not found.

- ↑ ۶۲.۰ ۶۲.۱ Jagodić 1998, para. 29.

- ↑ Sabit Uka (2004). Dëbimi i Shqiptarëve nga Sanxhaku i Nishit dhe vendosja e tyre në Kosovë:(1877/1878-1912)[The expulsion of the Albanians from Sanjak of Nish and their resettlement in Kosovo: (1877/1878-1912)]. Verana. pp. 194–286.

- ↑ Osmani, Jusuf (2000). Kolonizimi Serb i Kosovës Error in webarchive template: Check

|url=value. Empty. [Serbian colonization of Kosovo]. Era. pp. 48–50. - ↑ Osmani. Kolonizimi Serb. 2000. p. 43-64.

- ↑ ۶۶.۰ ۶۶.۱ Frantz, Eva Anne (2009). "Violence and its Impact on Loyalty and Identity Formation in Late Ottoman Kosovo: Muslims and Christians in a Period of Reform and Transformation." Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs. 29. (4) : 460–461. "In consequence of the Russian-Ottoman war, a violent expulsion of nearly the entire Muslim, predominantly Albanian-speaking, population was carried out in the sanjak of Niš and Toplica during the winter of 1877–1878 by the Serbian troops. This was one major factor encouraging further violence, but also contributing greatly to the formation of the League of Prizren. The league was created in an opposing reaction to the Treaty of San Stefano and the Congress of Berlin and is generally regarded as the beginning of the Albanian national movement. The displaced persons (Alb. muhaxhirë, Turk. muhacir, Serb. muhadžir) took refuge predominantly in the eastern parts of Kosovo. The Austro-Hungarian consul Jelinek reported in اپریل 1878.... The account shows that these displaced persons (muhaxhirë) were highly hostile to the local Slav population. But also the Albanian peasant population did not welcome the refugees, since they constituted a factor of economic rivalry. As a consequence of these expulsions, the interreligious and interethnic relations worsened. Violent acts of Muslims against Christians, in the first place against Orthodox but also against Catholics, accelerated. This can he explained by the fears of the Muslim population in Kosovo that were stimulated by expulsions of large Muslim population groups in other parts of the Balkans in consequence of the wars in the nineteenth century in which the Ottoman Empire was defeated and new Balkan states were founded. The latter pursued a policy of ethnic homogenisation expelling large Muslim population groups."

- ↑ Stefanović. Seeing the Albanians. 2005. p. 470. "The 'cleansing' of Toplica and Kosanica would have long-term negative effects on Serbian-Albanian relations. The Albanians expelled from these regions moved over the new border to Kosovo, where the Ottoman authorities forced the Serb population out of the border region and settled the refugees there. Janjićije Popović, a Kosovo Serb community leader in the period prior to the Balkan Wars, noted that after the 1876–8 wars, the hatred of the Turks and Albanians towards the Serbs 'tripled'. A number of Albanian refugees from Toplica region, radicalized by their experience, engaged in retaliatory violence against the Serbian minority in Kosovo. In 1900 Živojin Perić, a Belgrade Professor of Law, noted that in retrospect, 'this unbearable situation probably would not have occurred had the Serbian government allowed Albanians to stay in Serbia'. He also argued that conciliatory treatment towards Albanians in Serbia could have helped the Serbian government to gain the sympathies of Albanians of the Ottoman Empire. Thus, while both humanitarian concerns and Serbian political interests would have dictated conciliation and moderation, the Serbian government, motivated by exclusive nationalist and anti-Muslim sentiments, chose expulsion. The 1878 cleansing was a turning point because it was the first gross and large-scale injustice committed by Serbian forces against the Albanians. From that point onward, both ethnic groups had recent experiences of massive victimization that could be used to justify 'revenge' attacks. Furthermore, Muslim Albanians had every reason to resist the incorporation into the Serbian state."

- ↑ ۶۸.۰ ۶۸.۱ ۶۸.۲ ۶۸.۳ al-Arnaut, Muhamed Mufaku (1994). "Islam and Muslims in Bosnia 1878–1918: Two Hijras and Two Fatwās". Journal of Islamic Studies. 5. (2): 246–247. "As for Bosnia, the treaty signed at the congress of Berlin in 1878 stunned the Muslims of that country who did not believe that the Ottoman Empire would forsake them so easily, and did not docilely resign themselves to the new Austro-Hungarian rule. They set up a government for their own defence and fiercely resisted the Austro-Hungarian forces for about three months (29 July-20 اکتوبر 1878), a period which witnessed nearly sixty military clashes and resulted in 5000 casualties either killed or wounded." It may be noted that this stiff resistance was carried out almost exclusively by the Muslims, who were in this instance defending the homeland or vatan (Bosnia) and not the devlet (the Ottoman Empire) which forsook them. The Ottoman government had indeed seen in this resistance an opportunity to improve its own position and scored several points in its favour at the Istanbul Convention of 21 اپریل 1879. For example, it was emphasized that the fact of occupation constituted no infringement of the' sovereign rights of the sultan over Bosnia, that the Muslims had the right to maintain their ties with Istanbul, that the name of the sultan could be mentioned in the Friday prayer sermon and on similar occasions, and that the Ottoman flag could be raised on the mosques." But this new situation created such a nightmare that some elderly men preferred to confine themselves to their homes rather than see 'infidels' in the streets. The Muslims, who had not yet recovered from the 1878 shock, were taken aback by the new military service law of 1881 which applied to Muslim youths also. This increased dissatisfaction with the new situation and speeded up hijra to the Ottoman Empire."

- ↑ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Citation/CS1/COinS' not found.

- ↑ al-Arnaut. Islam and Muslims in Bosnia 1878–1918. 1994. p. 243. "As regards Bosnia, we have a hijra that deserves close attention, namely that which took place during the time of Ausrro-Hungarian rule (1878–1918) and evicted about 150,000 Muslims from Bosnia.[5] There are considerable differences in the estimates of the numbers of Bosnians emigrating to the Ottoman Empire during the period of Austro-Hungarian rule (1878–1915). The official statistics of the Austro-Hungarian administration admit that 61,000 Muslims emigrated, while Bogičević gives 150,000, Smlatić gives 160,000, and Imamović's estimate ranges between 150.000 and 180,000. Newspaper estimates rise to 300,000 and popular accounts put a figure as high as 700,000. Official statistics no doubt reduced the number of emigrants to make them equal the number of settlers who stayed in Bosnia (63,376). If we look at Ottoman data, we will find a wide gap between them and the Austro-Hungarian data. The Istanbul High Commissioners Office for Facilitating Refugee Settlement told Hiviz Bjelevac, the Bosnian writer, that during 1900–05 alone 73,000 Muslims left Bosnia, while Austro-Hungarian statistics give the much smaller number of 13,150. From all that has been said above, a figure like 150,000 will probably be more realistic. See Jovan Cvijić, 'o iseljavanju bosanskih muhamdanaca', Srpski književni glasnik XXIV, hr. 12, Beograd 16, VI, 1910, 966; Gaston Gravier, Emigracija Muslimana is BiH', Pregled, br. 7–8, Sarajevo 15. 1. 1911, 475; Vojslav Bogicević, Emigracija muslimana Bosnei Hercegovine u Tursku u doba austro-ugarske vladavine 1878–1918', Historijski zbornik 1–4, Zagreb 1958, 175–88; Mustafa Imamović, Pravni poloj i unutrašnjo-polički razvitak BiH od 1878–1914 (Sarajevo, 1976), 108–33; Dževat Juzbalić, Neke napomene o problemtici etničkog i društvenog razviska u Bosne i Hercegovine u periodu austro-ugarake uprave', Prilozi br. 11–12 (Sarajevo, 1976), 305; Iljaz Hadžibegovi, 'Iseljavanje iz Bosne i Hercegovine za vrijeme austro-ugarske uprave (1878 do 1918)', in Iseljaništvo naroda i narodnosti Jugoslavije (Zagreb, 1978), 246–7; Sulejman Smlatić, 'Iselavanje jugoslovenskih Muslinana u Tursku i njihovo prilagodjavanje novoj sredini', ibid. 253–3; Mustafa lmamović, 'Pregled istorije genocida nad Muslimanima u jugoslovenskim zemljama', Glasnik SIZ, hr. 6 (Sarajevo 1991), 683–5."

- ↑ Grossman, David (2011). Rural Arab Demography and Early Jewish Settlement in Palestine: Distribution and Population Density during the Late Ottoman and Early Mandate Periods. Transaction Publishers. p. 70.

- ↑ Ibrahim al-Marashi. "The Arab Bosnians?: The Middle East and the Security of the Balkans". p. 4. https://web.archive.org/web/20200518155511/https://www.hks.harvard.edu/kokkalis/GSW3/Ibrahim_Al-Marashi.pdf. Retrieved on 2015-05-31.

- ↑ ۷۳.۰ ۷۳.۱ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Citation/CS1/COinS' not found.

- ↑ Henze 1992

- ↑ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Citation/CS1/COinS' not found.

- ↑ Ahmed 2013.

- ↑ L.V.Burykina. Pereselenskoye dvizhenie na severo-zapagni Kavakaz. Reference in King.

- ↑ Richmond 2008.

- ↑ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Citation/CS1/COinS' not found.

- ↑ "Velyaminov, Zass ve insan kafası biriktirme hobisi" (in tr). 2 ستمبر 2013. https://jinepsgazetesi.com/2013/09/velyaminov-zass-ve-insan-kafasi-biriktirme-hobisi/. Retrieved on 26 ستمبر 2020.

- ↑ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Citation/CS1/COinS' not found.

- ↑ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Citation/CS1/COinS' not found.

- ↑ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Citation/CS1/COinS' not found.

- ↑ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Citation/CS1/COinS' not found.

- ↑ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Citation/CS1/COinS' not found.

- ↑ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Citation/CS1/COinS' not found.

- ↑ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Citation/CS1/COinS' not found.

- ↑ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Citation/CS1/COinS' not found.

- ↑ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Citation/CS1/COinS' not found.

- ↑ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Citation/CS1/COinS' not found.

- ↑ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Citation/CS1/COinS' not found.

- ↑ ۹۲.۰ ۹۲.۱ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Citation/CS1/COinS' not found.

- ↑ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Citation/CS1/COinS' not found.

- ↑ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Citation/CS1/COinS' not found.

- ↑ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Citation/CS1/COinS' not found.

- ↑ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Citation/CS1/COinS' not found.

- ↑ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Citation/CS1/COinS' not found.

- ↑ ۹۸.۰ ۹۸.۱ Allied Commission, Atrocités Grecques en Turquie, 1921.

- ↑ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Citation/CS1/COinS' not found.

- ↑ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Citation/CS1/COinS' not found.

- ↑ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Citation/CS1/COinS' not found.

- ↑ "Arşiv Belgelerine Göre Balkanlar'da ve Anadolu'da Yunan Mezâlimi 2". Scribd.com. 2011-01-03. https://web.archive.org/web/20131202233856/http://www.scribd.com/doc/46207420/Ar%C5%9Fiv-Belgelerine-Gore-Balkanlar%E2%80%99da-ve-Anadolu%E2%80%99da-Yunan-Mezalimi-2. Retrieved on 2013-09-07.

- ↑ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Citation/CS1/COinS' not found.

- ↑ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Citation/CS1/COinS' not found.

- ↑ Naimark 2002, p. ۴۶.

- ↑ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Citation/CS1/COinS' not found.

- ↑ Mango, Atatürk, p. 343.

- ↑ Naimark 2002, p. ۴۵.

- ↑ Housepian, Marjorie. "The Smyrna Affair". New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1966, p.153

- ↑ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Citation/CS1/COinS' not found.

- ↑ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Citation/CS1/COinS' not found.

- ↑ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Citation/CS1/COinS' not found.

- ↑ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Citation/CS1/COinS' not found.

- ↑ Auron, Yair. The Banality of Denial: Israel and the Armenian Genocide. New Brunswick, N.J.: Transaction Publishers, 2003, p. 248.

- ↑ Charny, Israel W. Encyclopedia of Genocide, Vol. 2. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO, 1999, p. 163.

- ↑ Hovannisian, Richard G. "Denial of the Armenian Genocide in Comparison with Holocaust Denial" in Remembrance and Denial: The Case of the Armenian Genocide. Richard G. Hovannisian (ed.) Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1999, p. 210.

- ↑ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Citation/CS1/COinS' not found.

- ↑ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Citation/CS1/COinS' not found.

- ↑ ۱۱۹.۰ ۱۱۹.۱ Mann, Michael (2005). The dark side of democracy: explaining ethnic cleansing. Cambridge University Press. p. 113. سانچہ:آئی ایس بی این. "In the Balkans all statistics of death remain contested. Most of the following figures derive from McCarthy (1995: 1, 91, 161–4, 339), who is often viewed as a scholar on the Turkish side of the debate. Yet even if we reduced his figures by as much as 50 percent, they would still horrify. He estimates that between 1811 and 1912, somewhere around 5 1/2 million Muslims were driven out of Europe and million more were killed or died of disease or starvation while fleeing. Cleansing resulted from Serbian and Greek independence in the 1820s and 1830s, from Bulgarian independence in 1877, and from the Balkan wars culminating in 1912."

- ↑ Door Michael M. Gunter. Armenian History and the Question of Genocide. Palgrave Macmillan, 2011, p. 127

- ↑ Door Natasha مئی Azarian. The Seeds of Memory: Narrative Renditions of the Armenian Genocide Across. ProQuest, 2007, p. 14: "...the leading Pro-Turkish academic"

- ↑ Bloxham. The Great Game of Genocide, p. 210. "Some of McCarthy's work considers the great population changes of the period, including extensive examination of the expulsion of Muslims from the new Balkan states and the overall demographic catastrophes of 1912–23... McCarthy's work has something to offer in drawing attention to the oft-unheeded history of Muslim suffering and embattlement that shaped the mindset of the perpetrators of 1915. It also shows that vicious ethnic nationalism was by no means the sole preserve of the CUP and its successors."

- ↑ ۱۲۳.۰ ۱۲۳.۱ Beachler, Donald W. (2011). The genocide debate: politicians, academics, and victims. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 123. سانچہ:آئی ایس بی این. "Justin McCarthy has, along with other historians, provided a necessary corrective to much of the history produced by scholars of the Armenian genocide in the United States. McCarthy demonstrates that not all of the ethnic cleansing and ethnic killing in the Ottoman Empire in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries followed the model often posited in the West, whereby all the victims were Christian and all the perpetrators were Muslim. McCarthy has shown that there were mass killings of Muslims and deportations of millions of Muslims from the Balkans and the Caucasus over the course of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. McCarthy, who is labeled (correctly in this author's estimation) as being pro- Turkish by some writers and is a denier of the Armenian genocide, has estimated that about 5.5 million Muslims were killed in the hundred years from 1821–1922. Several million more refugees poured out of the Balkans and Russian conquered areas, forming a large refugee (muhajir) community in Istanbul and Anatolia."

- ↑ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Citation/CS1/COinS' not found. "In the period between 1878 and 1912, as many as two million Muslims emigrated voluntarily or involuntarily from the Balkans. When one adds those who were killed or expelled between 1912 and 1923, the number of Muslim casualties from the Balkan far exceeds three million. By 1923 fewer than one million remained in the Balkans."

- ↑ ۱۲۵.۰ ۱۲۵.۱ ۱۲۵.۲ ۱۲۵.۳ ۱۲۵.۴ ۱۲۵.۵ ۱۲۵.۶ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Citation/CS1/COinS' not found.

- ↑ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Citation/CS1/COinS' not found.

- ↑ ۱۲۷.۰ ۱۲۷.۱ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Citation/CS1/COinS' not found.

- ↑ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Citation/CS1/COinS' not found.

- ↑ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'Module:Citation/CS1/COinS' not found.

- ↑ scrinia slavonica 12 (2012), 21–26. 21. Nedim Zahirović "U gradu Požegi postojalo je osamdesetih godina 16. stoljeća 10–11 islamskih bogomolja, a 1666. godine 14–15"

- ↑ Levene, Mark (2005), "Genocide in the Age of the Nation State" pp. 225–226

- ↑ "Georgian Diaspora – Calendar". https://web.archive.org/web/20171002121628/http://www.diaspora.gov.ge/index.php?lang_id=ENG&sec_id=124&info_id=2698.

ذرائع

سودھو- Stanford J. Shaw, Ezel Kural Shaw، ہسٹری آف دی عثمانی سلطنت تے جدید ترکی ، کیمبرج یونیورسٹی پریس، ۱۹۷۷،سانچہ:آئی ایس بی این

- ایلن ڈبلیو فشر، کریمین تاتار ، ہوور پریس، ۱۹۷۸،سانچہ:آئی ایس بی این

- والٹر رچمنڈ، سرکیشین نسل کشی ، رٹجرز یونیورسٹی پریس، ۲۰۱۳،سانچہ:آئی ایس بی این

- الیگزینڈر لابن ہنٹن، تھامس لا پوائنٹ، پوشیدہ نسل کشی ، ڈگلس ارون-ایرکسن، رٹگرز یونیورسٹی پریس، ۲۰۱۳،سانچہ:آئی ایس بی این

- ایریکا چینوتھ، ایڈریا لارنس، تشدد اُتے نظر ثانی، ایم آئی ٹی پریس، ۲۰۱۰،سانچہ:آئی ایس بی این

- کلیجدہ ملاج، نسلی صفائی دی سیاست ، لیکسنگٹن کتاباں، ۲۰۰۸،سانچہ:آئی ایس بی این

- جان دے کاکس، سربیا دی تریخ ، گرین ووڈ پبلشنگ گروپ، ۲۰۰۲،سانچہ:آئی ایس بی این

- Igor Despot, The Balkan Wars in the Eyes of Warring Party, iUniverse, 2012,سانچہ:آئی ایس بی این

- ڈگلس آرتھر ہاورڈ، ترکی دی تریخ ، گرین ووڈ پبلشنگ گروپ، ۲۰۰۱،سانچہ:آئی ایس بی این

- بینجمن لیبرمین، ٹیریبل فیٹ: ایتھنک کلینجنگاݪ انہاں دتی میکنگ آف ماڈرن یورپ ، روومین اینڈ لٹل فیلڈ، ۲۰۱۳،سانچہ:آئی ایس بی این

- جان جوزف، مسلم-مسیحی تعلقات تے بین مسیحی دشمنیاں ، SUNY پریس، ۱۹۸۳،سانچہ:آئی ایس بی این

- وکٹر روڈومیٹوف، نیشنلزم، گلوبلائزیشن، تے آرتھوڈوکس ، گرین ووڈ پبلشنگ گروپ، ۲۰۰۱،سانچہ:آئی ایس بی این

- چارلس جیلاوچ، دی اسٹیبلشمنٹ آف دی بلقان نیشنل اسٹیٹس ، ۱۸۰۴-۱۹۲۰، یونیورسٹی آف واشنگٹن پریس، ۱۹۸۶،سانچہ:آئی ایس بی این

- ثریا فاروقی، دی کیمبرج ہسٹری آف ترکی ، کیمبرج یونیورسٹی پریس، ۲۰۰۶،سانچہ:آئی ایس بی این

- ریان جنجراس، سوروفول شورز ، آکسفورڈ یونیورسٹی پریس، ۲۰۰۹،سانچہ:آئی ایس بی این

- Ugur Ümit Üngör، جدید ترکی دی تشکیل ، آکسفورڈ یونیورسٹی پریس، ۲۰۱۱،سانچہ:آئی ایس بی این

- اسٹینلے ایلفنسٹون کیر، دی لائنز آف ماراش ، SUNY پریس، ۱۹۷۳،سانچہ:آئی ایس بی این